The Unicorn in Captivity the Unicorn in Captivity Art

Tapestry ane, The Unicorn is Establish

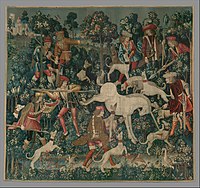

The Hunt of the Unicorn or the Unicorn Tapestries (French: La Chasse à la licorne ) is a series of vii tapestries made in the S Netherlands around 1495–1505, and now in The Cloisters in New York. They were possibly designed in Paris and show a grouping of noblemen and hunters in pursuit of a unicorn through an idealised French landscape. The tapestries were woven in wool, metallic threads, and silk. The vibrant colours, still axiomatic today, were produced from dye plants: weld (xanthous), madder (red), and woad (blue).[ane]

Kickoff recorded in 1680 in the Paris domicile of the Rochefoucauld family, the tapestries were looted at the French Revolution. Rediscovered in a befouled in the 1850s, they were hung at the family'due south Château de Verteuil. Since then they take been the subject of intense scholarly debate about the pregnant of their iconography, the identity of the artists who designed them, and the sequence in which they were meant to be hung. Although various theories have been put forward, as yet nothing is known of their early history or provenance, and their dramatic merely conflicting narratives have inspired multiple readings, from chivalric to Christological. Variations in size, style, and limerick suggest they come up from more than ane set,[two] linked past their subject area matter, provenance, and the mysterious AE monogram which appears in each. One of the panels, "The Mystic Capture of the Unicorn", survives every bit simply two fragments.[3]

James J. Rorimer speculated in 1942 that the tapestries were commissioned by Anne of Brittany,[four] to gloat her spousal relationship to Louis XII, King of France in 1499.[5] Rorimer interpreted the A and E monogram that appears in each tapestry as the first and the terminal letters of Anne's proper name.[half-dozen] Margaret B. Freeman, however, rejected this interpretation in her 1976 monograph,[7] a determination repeated by Adolph South. Cavallo in his 1998 piece of work.[8] Tom Campbell, former Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, recently acknowledged that experts "still do not know for whom or where [the tapestries] were made." And so far, scholarly efforts to explain the AE and other inscriptions, to place the few heraldic symbols, and to coherently account for the puzzling narratives take met with limited success.

Themes [edit]

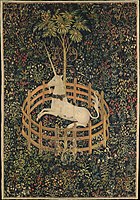

The Unicorn is in Captivity and No Longer Dead

One theory is that the tapestries show pagan and Christian symbolism. The infidel themes emphasise the medieval lore of beguiled lovers, whereas Christian writings interpret the unicorn and its death as the Passion of Christ. The unicorn has long been identified past Christian writers as a symbol of Christ, conscripting the traditionally pagan symbolism of the unicorn. The original pagan myths almost The Hunt of the Unicorn refer to an animal with a single horn that can only exist tamed by a virgin; Christian scholars translated this into an allegory for Christ's relationship with the Virgin Mary.

In the Gothic tapestry, the makers considered biblical events every bit historical, and linked the biblical and secular narratives in the tapestry weaving.[nine] Medieval art illustrated moral principles,[10] and the tapestries used narrative allegories to illustrate these morals. The secular unicorn hunt was non but Christian art, only also an allegorical representation of the Proclamation.[11]

Acknowledging Rorimer'southward speculation that the tapestries were commissioned to celebrate a marriage, Freeman noted that medieval poets connected the taming of the unicorn to the devotion and subjugation of love. The taming of the unicorn symbolises the secular lover or mate who was enchained by a virgin and entrapped in the argue (in the tapestry The Unicorn in Captivity). In add-on, the author pointed out that the concept of an overlapping God of Heaven and God of love was accepted in the belatedly Middle Ages.[12]

The making of the tapestries [edit]

Tapestry 6: The Unicorn is Killed and Brought to the Castle

Questions about the original workmanship of the tapestries remain unanswered. The design of the tapestries is rich in figurative elements similar to those found in oil painting. Apparently influenced by the French mode,[13] the elements in the tapestries reflect the woodcuts and metalcuts fabricated in Paris in the late fifteenth century.[14]

The garden backgrounds of the tapestries are rich in floral imagery, featuring the "millefleurs" background style of a variety of small botanic elements. Invented by the weavers of the Gothic historic period, it became popular during the tardily medieval era and declined after the early Renaissance.[15] There are more than a hundred plants represented in the tapestries, scattered beyond the green backgrounds of the panels, eighty-five of which have been identified by botanists.[xvi] The particular flowers featured in the tapestries reverberate the tapestries' major themes. In the unicorn series, the hunt takes place within a Hortus conclusus, literally meaning "enclosed garden," which was not only a representation of a secular, physical garden, but a connexion with the Announcement.

The Unicorn is Killed and Brought to the Castle, detail

The tapestries were very probably woven in Brussels, which was an of import eye of the tapestry manufacture in medieval Europe. An example of the remarkable piece of work of the Brussels looms, the tapestries' mixture of silk and metallic thread with wool gave them a fine quality and vivid color. The wool was widely produced in the rural areas around Brussels, and a common primary material in tapestry weaving. The silk, however, was costly and hard to obtain, indicating the wealth and social condition of the tapestry owner.

Subjects [edit]

The seven tapestries are:[17]

- "The Start of the Hunt"

- "The Unicorn at the Fountain"

- "The Unicorn Attacked"

- "The Unicorn Defending Himself"

- "The Unicorn Captured by the Virgin" (two fragments)

- "The Unicorn Killed and Brought to the Castle"

- "The Unicorn in Captivity"

The tapestries comprise v large pieces, one modest piece, and ii fragments.[18]

The mobility associated with the size formed an essential consideration of the function of the tapestry in the medieval age and dissimilar sizes of Gothic tapestries served equally the decoration to fit chosen walls in the centre historic period.[19] In the modernistic research, based on the possibility that the unicorn tapestries were designed for use every bit a bedroom ensemble, the five big pieces fit the back area of wall, while the other ii pieces serve as the coverlet, or overhead canopy.[20]

Other sources give slightly different titles and dissimilar sequences. The factors that touch on this are primarily threefold. Firstly the nature of the tapestries themselves, which showroom differences of manufacture and size, suggesting that the first and last may exist independent works or form a unlike series. Secondly the nature of the archetype stag hunt, usually cited to Livre de la Chasse by Gaston III, Count of Foix.[21] Thirdly the established story of the unicorn hunt, where the unicorn is made docile by a virgin, and so captured, wounded or killed. In addition the symbolism of the story needs to be taken into account.

Provenance [edit]

The tapestries were owned by the La Rochefoucauld family unit of French republic for several centuries, with first mention of them showing up in the family'due south 1728 inventory. At that fourth dimension v of the tapestries were hanging in a bedroom in the family's Château de Verteuil, Charente and two were stored in a hall side by side to the chapel. The tapestries were highly believed woven for François, the son of Jean II de La Rochefoucauld and Marguerite de Barbezieux. And there was a possible connectedness betwixt the letters A and E and the La Rochefoucauld, which are interpreted as the beginning and last of Antoine's name, who was the son of François, and his wife, Antoinette of Amboise.[14] During the French Revolution the tapestries were looted from the château and reportedly were used to cover potatoes – a menses during which they apparently sustained damage. By the stop of the 1880s they were over again in the possession of the family. A visitor to the château described them as quaint 15th century wall hangings, still showing "incomparable freshness and grace". The aforementioned visitor records the fix as consisting of seven pieces, though ane was by that time in fragments and existence used as bed defunction.[22]

John D. Rockefeller Jr. bought them in 1922 for about one million US dollars.[23] 6 of the tapestries hung in Rockefeller's house until The Cloisters was built when he donated them to the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art in 1938 and at the same fourth dimension secured for the collection the two fragments the La Rochefauld family had retained. The gear up at present hangs in The Cloisters which houses the museum's medieval collection.[24]

Restoration [edit]

In 1998 the tapestries were cleaned and restored. In the process, the linen backing was removed, the tapestries were bathed in water, and it was discovered that the colours on the back were in fifty-fifty better condition than those on the forepart (which are also quite vivid). A series of high resolution digital photographs were taken of both sides using a customised scanning device suspending a linear array scan camera and lighting over the fragile textile. The forepart and dorsum of the tapestries were photographed in approximately three-by-iii-pes square segments. The largest tapestry required up to 24 individual 5000 × 5000 pixel images. Merging the massive data stored in these photos required the efforts of 2 mathematicians, the Chudnovsky brothers.

Recreation [edit]

Historic Scotland deputed a set of vii hand-fabricated tapestries for Stirling Castle, a recreation of The Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries, as part of a project to furnish the castle as it was in the 16th century. It was part-funded by the Quinque Foundation of the Us.

All seven currently hang in the Queen'southward Inner Hall in the Royal Palace.[25]

The tapestry projection was managed by West Dean College in Westward Sussex and piece of work began in January 2002. The weavers worked in two teams, 1 based at the higher, the other in a purpose-built studio in the Nether Bailey of Stirling Castle.[26] The starting time three tapestries were completed in Chichester, the remainder at Stirling Castle.

Historians studying the reign of James IV believe that a similar serial of "Unicorn" tapestries were part of the Scottish Royal tapestry collection. The team at West Dean Tapestry visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art to inspect the originals and researched the medieval techniques, the colour palette and materials.[27] Traditional techniques and materials were used with mercerised cotton taking the place of silk to preserve its color better.[25] The wool was specially dyed at Due west Dean College.[28]

In popular culture [edit]

- In 1961, Leonard Cohen published The Spice Box of Earth, a drove of poems including "The Unicorn Tapestries".

- The opening sequence of the 1982 animated movie The Last Unicorn was designed in reference to the tapestries, with many elements such every bit the fountain and lions, as well as the overall style beingness extremely similar.

- The seventh tapestry in the serial ("The Unicorn in Captivity") appears briefly in Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince, adorning the wall of a corridor near the Room of Requirement and the tapestry is seen in the various mutual rooms (Gryffindor, Slytherin, Ravenclaw, and Hufflepuff) with different coloured backgrounds. Too appears in the movie Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. At Universal Studios in Los Angeles and Orlando replicas of this tapestry can exist see adorning the wall in the queue for the Forbidden Journey ride which replicates the interior of the Hogwarts Castle.

- It appears in Spider-Homo: Far From Habitation in the art room of the school. In the shot of MJ's (Zendaya) first advent The Unicorn in Captivity tin can be spotted in the upper right corner.

- It appears in Rumpelstiltskin's castle in One time Upon a Time.

- It appears in the episode "The Lich" in Season iv of Hazard Time.

- It appears above Stewie'southward cot in the episode "Chap Stewie" of flavor 12 of Family unit Guy.

- It appears in BoJack Horseman in S2E2

- The tapestry "The Unicorn is Found" appears in one of the concluding scenes in the film Ghosts of Girlfriends Past.

- It appears in the 1988 film Some Girls.

- It appears in the 1993 film The Secret Garden.

- In a French commercial for the cheese "Coeur de Panthera leo", which means "Lionheart". Pub Coeur de Lion – Moyen Historic period.

- A collage of the tapestry appears on the cover of the music album The Mask and Mirror by Canadian composer-musician Loreena McKennitt.

- The tapestries' millefleur were adapted and redesigned past artist Leon Coward for the mural The Happy Garden of Life in the 2016 sci-fi movie 2BR02B: To Be or Nix to Exist every bit part of the mural's religious allusions.[29] The flowers are modeled on those in The Unicorn in Captivity.

- Elementary school readers of Mary Pope Osborne'due south popular Magic Tree House series are introduced to the tapestries and the Cloisters Museum in Blizzard of the Blueish Moon.

- The tapestries are the subject matter of Samuel R. Delany's brusque story "Tapestry," constitute in Aye, and Gomorrah, and other stories.

- Information technology appears in a seventh-season episode of The Venture Brothers, which is also named after the tapestry.

- "The Unicorn in Captivity" is displayed in Sabrina'due south house in the 2018 TV series The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina (best seen in episode nine).

- "The Unicorn in Captivity" is displayed in Niles Caulder's house in the 2019 Telly serial Doom Patrol (best seen in episode seven).

- The tapestries are mentioned in the 1982 novel Annie on My Heed in which the primary characters come across and hash out the tapestries while visiting The Cloisters Museum.

Gallery [edit]

-

The Hunters Enter the Woods

-

The Unicorn is Plant

-

The Unicorn is Attacked

-

The Unicorn Defends Itself

-

The two Fragments of The Mystic Capture of the Unicorn

-

The Unicorn is Killed and Brought to the Castle

-

The Unicorn is in Captivity and No Longer Dead

Run across as well [edit]

- The Lady and the Unicorn, some other series of unicorn tapestries from the same period

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ "How the Tapestries Came to the Met". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 7 May 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ Colburn, Kathrin (2010). "3 Fragments of the 'Mystic Capture of the Unicorn' Tapestry" (PDF). Metropolitan Museum Periodical. 45: 97–106 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Technically, there were iii fragments, i of which much smaller than the others, which has since been joined with the rightmost fragment. Colburn, Kathrin (2010). "3 Fragments of the 'Mystic Capture of the Unicorn' Tapestry" (PDF). Metropolitan Museum Journal. 45: 97–106 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Rorimer, James J. (Summer 1942). "The Unicorn Tapestries were made for Anne of Brittany" (PDF). The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art Bulletin. doi:10.2307/3257087. JSTOR 3257087. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Campbell, Thomas P. (2002). Tapestry in the Renaissance: Art and Magnificence. The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. p. 73. ISBN1588390225 . Retrieved nine January 2018.

- ^ Freeman 1983, p. 156.

- ^ Freeman, Margaret B. (1976). The Unicorn Tapestries. Metropolitan Museum of Art/Dutton. pp. 156 ff. ISBN0-525-22643-v.

- ^ Cavallo 1998, p. 21.

- ^ Verlet 1978, p. xix.

- ^ Verlet 1978, p. 22.

- ^ Schiller, Gertrud (1971). Iconography of Christian Art. London: Lund Humphries Publishers Express. p. 53. ISBN0-85331-270-two.

- ^ Freeman 1983, p. 53.

- ^ Verlet 1978, p. 26.

- ^ a b Freeman, Margaret B. (1973–1974). "The Unicorn Tapestries". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Message. 32 (1). JSTOR 3258590.

- ^ Verlet 1978, p. 15.

- ^ Freeman 1983, p. 111.

- Alexander, E. J.; Woodward, Carol H. (1941). "The Flora Of The Unicorn Tapestries". Journal of the New York Botanical Garden. 42 (497): 105–122.

- Alexander, Eastward. J.; Woodward, Carol H. (1941). "Check-List Of Plants In The Unicorn Tapestries". Journal of the New York Botanical Garden. 42 (498): 141–147.

- ^ Alexander, Eastward. J.; Woodward, Carol H. (May 1941). "The Flora of the unicorn tapestries". Journal of the New York Botanical Garden. 42 (497).

- ^ Verlet 1978, p. 24.

- ^ Verlet 1978, p. 13.

- ^ Freeman, Margaret B. (2010). "The Unicorn Tapestries". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin.

- ^ Bibliotheque National, Paris, Ms. fr. 616

- ^ Freeman 1983, pp. 223–4.

- ^ Preston, Richard (11 Apr 2005). "Capturing the Unicorn". The New Yorker . Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ Cavallo 1998, p. 15.

- ^ a b "The Stirling Tapestries". Stirling Castle. Archived from the original on 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Day Fourteen, 29 April 2013". Singing Weaver. thirteen May 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Celebrated Scotland". West Dean Tapestry Studio. The Edward James Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- ^ "Stirling Tapestries Factsheets". Historic Scotland. 26 June 2008. Archived from the original on 2 Apr 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Masson, Sophie (xix Oct 2016). "2BR02B: the journeying of a dystopian motion picture–an interview with Leon Coward". Feathers of the Firebird (Interview).

Bibliography [edit]

- Cavallo, Adolph S. (1998). The Unicorn Tapestries at the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN978-0-87099-868-3.

- Freeman, Margaret B. (1983). The Unicorn Tapestries . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. ISBN0-87099-147-seven.

- Verlet, Pierre (1978). The book of tapestry: history and technique. London: Octopus Books. ISBN0-7064-0961-2.

Further reading [edit]

- Freeman, Margaret B. (May 1949). "A New Room for the Unicorn Tapestries" (PDF). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Message. 7 (nine). doi:10.2307/3257359. JSTOR 3257359.

- Nickel, Helmut (1982). "Well-nigh the Sequence of the Tapestries in The Chase of the Unicorn and The Lady with the Unicorn". Metropolitan Museum Periodical. 17. doi:10.2307/1512782. JSTOR 1512782. S2CID 191400878.

External links [edit]

- Unicorn tapestries in the drove of the MET

- Jow, Tiffany (27 July 2017). "Why the Mystery of the Famous Unicorn Tapestries Remains Unsolved". Artsy . Retrieved three August 2017.

- The Hunt and The Cloisters, Temple of the Lord's day

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Hunt_of_the_Unicorn

0 Response to "The Unicorn in Captivity the Unicorn in Captivity Art"

Postar um comentário